Ikebana(生花) – The Japanese Art That’s Making a Comeback

October 26, 1975 Ikebana International. Kasumi Teshigahara. Photo by Denver Post via Getty Images.

What does ikebana look like?

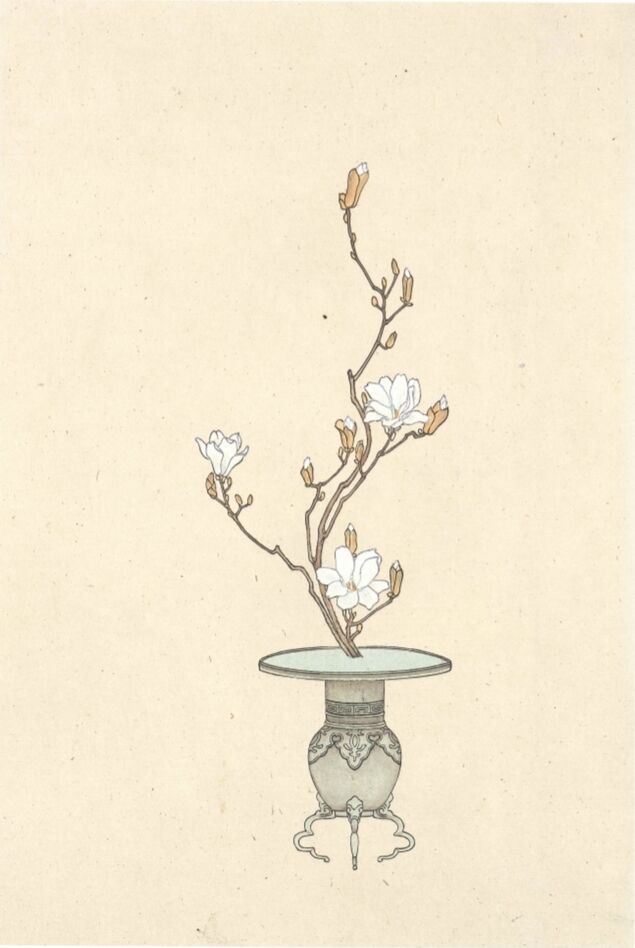

Ikebana arrangements are not unlike sculpture. Considerations of color, line, form, and function guide the construction of a work. The resulting forms are varied and unexpected, and can range widely in terms of size and composition, from a piece made from a single flower to one that incorporates several different flowers, branches, and other natural objects.

In Japanese culture, most native flowers, plants, and trees are embedded with symbolic meaning and are associated with certain seasons, so in traditional ikebana, both symbolism and seasonality have always been prioritized in developing arrangements. Some of the most common elements used are bamboo grass year round; pine and Japanese plum branches around the new year; peach branches for Girls Days in March; narcissus and Japanese iris in the spring; cow lily in summer; and chrysanthemum in autumn. Modern ikebana practices call for the same sensitivity to seasons, as well as to the environment in which an arrangement is being made.

Sometimes, practitioners of ikebana, or ikebanaists, trim flowers and branches into unrecognizable shapes, or they may even paint the leaves of an element. Plant limbs may be arranged to sprout into space in various directions, but in the end, the whole work must be balanced and contained. At times, arrangements are mounted in a vase, though this is not always the case.

In ikebana, it is not enough to have beautiful materials if the materials are not artfully employed to create something even more beautiful. Given a skilled maker, one carefully placed flower can be just as powerful as an elaborate arrangement.

Who practices ikebana?

Hirozumi Sumiyoshi, Rikka, ca. 1700. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Coloured diagram #15 ofshōkaworks by the 40th headmaster Ikenobō Senjō, from the Sōka Hyakki, 1820. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Ikebana can be practiced by both amateurs and professionals, both of whom are able to achieve elegant results. However, like many other art forms, mastering the basics is fundamental to any practice, and only then can a person begin to experiment.

Guided by precision, a core value of Japanese culture, beginners are taught basic technical skills—like how to properly cut branches and flowers, how to measure angles in space for the correct placement of branches and stems, and how to preserve live materials—along with the etiquette of maintaining a clean work station.

Beginners are also taught how to sensitize their eyes to the materials, to be able to bring out their inner qualities, and understand how this changes with each arrangement. Beginner arrangements done in the Nageire and Moribana styles often make use of two tall branches and a small bundle of flowers. These pieces follow the three-stem system of shin, soe, and hikae—elements that have traditionally represented heaven, man, and Earth, respectively. Now, on a practical level, they refer to the main stems that are employed. All other stems are called jushi, meaning supporting or subordinate stem.

How is a basic ikebana arrangement made?

Photo by Annie Dalbéra, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo by Annie Dalbéra, via Wikimedia Commons.

To prepare a basic Moribana arrangement, for example, the ikabanaist adds water to a shallow container, then places a kenzan—a small, pin-covered object that keeps flowers in place—within it. Then, the maker selects two branches, one for shin and one for soe, and a flower, for hikae. Next, each stem is measured and cut to precise lengths (which are specified in the Moribana beginner’s manual) and fixed, one at a time, on the kenzan, at different angles. To complete the arrangement, supplementary jushi stems are added to hide the kenzan and fill out the arrangement. These principles can be repeated over and over, shifting the placement and angles to achieve different shapes and effects.

The beginnings of ikebana

Photo by Carlos Donderis, via Flickr.

The roots of ikebana in Japan are believed to trace back to either the ceremonial practices of the native Shinto religion, or to a tradition of making floral offerings in Buddhism, which was imported from China in the 6th century.

The first known written text on ikebana, called Sendensho, was penned in the 15th century. In it, readers find a thorough set of instructions on how to create arrangements that are appropriate to certain seasons and occasions; its directives make clear that the practice of ikebana embodies the evolved appreciation and sensitivity to nature that Japanese culture is known for more broadly.

Around the same time, ikebana started to become a secular activity. The design of the Japanese home during this period reflects this transition: new homes were almost always built with a special recess called the tokonoma, which would contain a scroll, a precious art object, and a flower arrangement.

Amidst the muted colors and flat planes of the traditional Japanese home, the tokonoma stood out as the singular place for color and decoration, and deep consideration was given to the objects placed there. In keeping with the Japanese culture’s reverence for impermanence, tokonoma displays were rotated regularly, with the changing seasons and during festive occasions. Arranging flowers in this context paved the way for ikebana and its recognition as a distinct art form.

The traditional schools of ikebana

Photo by Carlos Donderis, via Flickr.

Photo by Carlos Donderis, via Flickr.

In the 15th century, with the sudden ubiquity of the tokonoma and teachings of the Sendensho, ikebana practices began to flourish. First came the rise of the Ikenobo School, whose name refers to a long line of priests in Kyoto who followed the Buddhist tradition of presenting floral offerings in the temple. During this time, Ikenobo Senkei gained fame for his skillful floral compositions; today, he is considered the first master of ikebana.

The secular style that Senkei practiced became known as Rikka, which means “standing flowers.” This type of ikebana is made with seven core elements (or sometimes nine), which are a mix of tree branches and two or three flowers—pine, chrysanthemum, irises, and boxwood are commonly used. These elements are combined, traditionally in an ornate Chinese vase, to create bursting, triangular shapes, with tall elements at the center and shorter ones shooting outwards. To be able to make the main elements stand upright without support requires a high level of technical skill. Rikka compositions are considered the most grand, but also the most rigid (even by today’s standards). They were originally intended for temples and later found in royal palaces and the stately homes of the rich.

At the same time, a more modest approach to flower arrangement was also gaining popularity as an extension of Zen Buddhism and the Wabi-Sabi and Tea Ceremony aesthetics that grew from its core tenets. Japan’s most famous tea master, Sen no Rikyū, introduced an appreciation for imperfect, modest aesthetics in his tea ceremonies, which included the use of flowers. Rather than constructing over-the-top Rikka-style arrangements, Rikyū preferred minimalist, single-stem arrangements, like one morning glory placed in a simple vase made by a local artisan. These ceremonies led to the formation of the second major style ikebana, which came to be known as Nageire, meaning “thrown in.”

In its early form, Nageire was free of the rules and formality that governed the Rikka style. As the antithesis to Rikka, flowers in Nageire arrangements were not designed to stand upright on their own and were instead placed in tall vases that supported the stems of the flowers.

Rikka and Nageire represent two opposing viewpoints. Rikka, though technically a secular style, concerns itself with the the cosmos, harking back to its Buddhist origins. In contrast, Nageire’s more organic approach focuses more directly on connections with nature.

Modern schools of ikebana

Installation view of Nendo, Kaleidoscopic Ivy, 2017 in collaboration wtih hnm, syk + onndo. Photo by Akihiro Yoshida. Courtesy of Nendo.

Due to over 200 years of political isolation in Japan, there were no further innovations in ikebana until 1868, when the country reopened to foreign exchange. People were quick to embrace Western customs, and in the world of ikebana, this catalyzed a series of radical changes.

In 1912, the first modern school of ikebana, the Ohara School, was established. Its founder, Unshin Ohara, helped the art form evolve by introducing the Moribana style, and through it, implementing two major changes: the incorporation of Western flowers, and the use of a shallow, circular container to make flowers stand upright, with the help of the kenzan.

The flexibility and variation that the Moribana style allows for has made it a favorite and a staple in almost every ikebana school today. At the core of Moribana is a three-stem system, whereby three flowers are almost always fixed to create a triangle. Compositions that do not follow this triangle system are known as freestyle. Freestyle is also used to describe more creative and original approaches to ikebana, where the maker uses their knowledge of form, color, and line from previous practice to develop new arrangements that don’t necessarily adhere to traditions.

Changes continued with the creation of the Sogetsu School in 1927. Its founder, Sofu Teshigahara (whose father was also an ikebana master), is credited with elevating ikebana from a technical practice to an art at the level of sculpture, which is how it is has been viewed ever since.

Teshigahara’s approach called for greater freedom and the use of other live materials. For him, the forgotten parts of nature—like dirt, rocks, and moss—were just as ripe with expressive potential as flowers. He heartily believed that excellent ikebana is not divorced from the life and times of its creator, and that a flower is an irreplaceable, expressive tool that reveals the soul. With these innovations, the Rikka style began to fade. At present, Ikenobo, Ohara, and Sogetsu are the most popular styles, with around 400 of these schools operating today.

Ikebana today

In the mid-20th century, the internationalization of ikebana was spurred by the efforts of Ellen Gordon Allen, an American who studied ikebana while living in Japan. She saw ikebana as a means of uniting people from around the world. Beginning in 1956, Allen worked with the major ikebana schools to found a nonprofit organization called Ikebana International, which would propel a diplomatic mission: “friends through flowers.”

In the decades since, chapters for all the major schools have sprouted up on a global scale. In recent years, the practice has inspired contemporary artists like Camille Henrot and a wide swath of floral artists, who use the tenets of ikebana to develop new, original creations.

Anyone who practices ikebana today knows well that building relationships is at the core of the practice—relationships between materials, between students, and between teachers and their pupils.

In Japan today, the word kado, meaning “way of flowers,” is the preferred term for ikebana, as it’s believed to more accurately capture the spirit of the art as a lifelong path of learning. The impermanence built into this art, beginning with its dependence on nature’s seasons, lends itself to never-ending exploration and experimentation for ikebanaists.

Teshigahara was firm in his conviction that a successful lifelong ikebana practice requires curiosity, not complacency. “We must strive to develop into artists with breadth and depth instead of remaining comfortable in our artistic niche,” he once said. “Our creations should vary. If we do not venture out we will never become outstanding artists.”